Kids are natural scientists. Why aren’t more adults?

By Asa Stahl | January 12, 2023

A graduate student is about to share his work in front of a live audience. He feels nervous, intimidated, and a little unprepared. His listeners have high standards and will not hesitate in their criticism.

They are, at most, six years old.

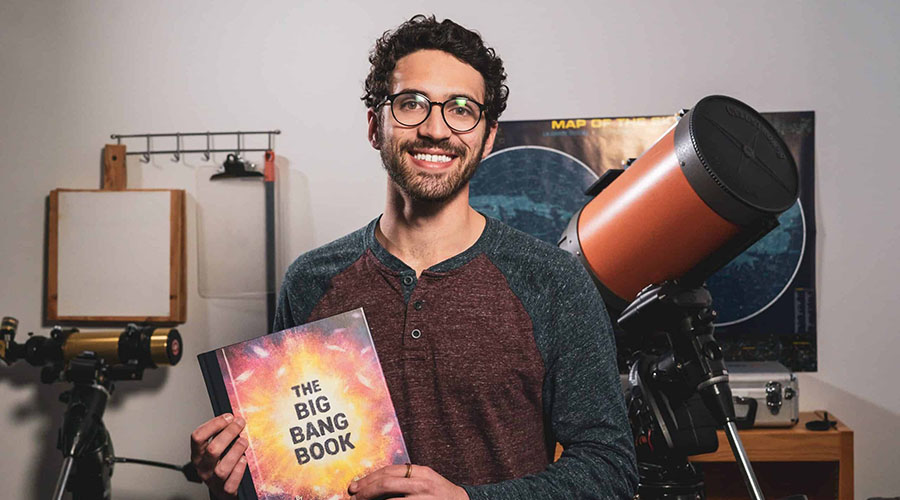

That was the first time I read my pop astronomy picture book, The Big Bang Book, to a group of children. Though it went well, what stuck with me most is the deluge of questions that came after the reading. In half an hour, a class of first-graders asked me more about astronomy than every adult I have met has, combined, over the course of my entire PhD.

I walked away from that school trying to understand why. If the common wisdom is that children are natural scientists, then what changes as they grow older?

I often see adults excited to meet physicists but unsure how to engage them. Some cast about for questions and come up empty, others think of questions but hold back for fear of looking ignorant, and many, though they like the idea of physics, will avoid it entirely because they see the field as closed to them.

The first-graders, on the other hand, were used to not knowing. The only obstacle they faced was shyness. Asking questions came naturally to them; they just had to be shown a little of what science has taught us to become excited about what they could learn.

Yet children don’t wonder about the world more than adults — so why don’t adults ask more questions?

Asa Stahl

I believe that we, as scientists, have too zealously staked our territory. In our effort to be known for providing answers, we have also defined ourselves as the only ones who ask questions.

There are two reasons for this. First, we mainly sell physics to adults through what our field can explain and do. Science communicators, understandably, focus on physics’ achievements, like the recent milestone of fusion ignition or the launching of Artemis I. We take the most exciting projects, describe them accessibly, and hope that it will not only momentarily engage people, but convert them into curious nerds like us — or at the very least, make them root more eagerly for science in the future.

At the same time, we are afraid of showing weakness. If the public frequently misinterprets our explanations, the thinking goes, then communicating what we don’t know could be even more disastrous. With every admission of uncertainty, debate, or ignorance, we could undermine our field’s authority.

Both these tendencies have profound drawbacks. Presenting results with overconfidence (or worse, defensiveness) can backfire because it builds distrust, as we saw during the pandemic. It’s true that some people will seize on any description of scientific uncertainty as evidence that none of us know anything — but that audience probably isn’t going to be convinced no matter what we say. On the contrary, playing it straight with the public could lead fewer people to become alienated.

At the same time, touting what physics has accomplished may attract interest in what we do — especially when it comes to momentous events, like the discovery of the Higgs boson — but it often confines science communication to neat explanations. In focusing on what we have learned, we risk presenting physics as a closed book. We lose the appeal of the unknown.

That sense of mystery and inquiry is the soul of physics, and it presents our best means of engaging the public. A professional physicist may have knowledge that a layperson doesn’t, but the two probably share some of the same questions. That’s common ground we can build on.

In this light, what we don’t know as physicists is not a liability — it’s a resource for relating with the public. The questions of physics are fundamental and universal, with a basic claim to everyone’s imagination. I remember, as a third-grader, seeing a poster in my math classroom that asked, “What shape is the universe?” The diagrams of outer space, fit within spheres, toruses, and saddles, boggled my mind. At that age, the world seemed immutable and so intentionally run by adults. How could grown-ups not know the answer to such a simple question?

Those gaps in knowledge let wonder into our lives. The more we can outline the frontiers of scientific understanding to the public, the better chance we have of connecting them with what we care about, and of closing the gap between scientists and laypeople.

If we can accomplish this, it won’t just be a victory for science communication. Our field is a shared endeavor for all humanity, meaning it progresses only as much as it’s widely understood. The work isn’t done until anyone who wants to can understand both the discoveries of physics and its mysteries.

That means we must reorient how we communicate science to strike a better balance between questions and answers. Whether a listener is six years old or sixty, we lose an opportunity when we pretend to know everything. Instead, we ought to show confidence in what we do know and excitement about what we don’t. Most of all, it means relinquishing some of our authority as scientists, taking a step down from the pedestal we’ve placed ourselves on, and admitting we are still learning — so that everyone else can feel comfortable learning, too.

Asa Stahl is a doctoral candidate in astrophysics at Rice University and the author of the award-winning children’s book, The Big Bang Book. He was a 2022 AAAS Mass Media Fellow for Science News; his fellowship was sponsored by APS.

The views expressed in interviews and in opinion pieces, like the Back Page, are not necessarily those of APS. APS News welcomes letters responding to these and other issues.

©1995 - 2024, AMERICAN PHYSICAL SOCIETY

APS encourages the redistribution of the materials included in this newspaper provided that attribution to the source is noted and the materials are not truncated or changed.

Editor: Taryn MacKinney

February 2023 (Volume 32, Number 2)

Articles in this Issue